Revolution@1: Sex and the citizen in Egypt and America

By Khaled Diab

Fundamentalists in America and Egypt are obsessed with “virtue “and “vice”. But the rise of Islamists threatens to bind Egyptian women in a moral vice.

Thursday 26 January 2012

It is a longstanding marketing truism that sex sells. But it (well, hostility towards it) doesn’t just market products, it can also be marshalled to sell wholly unsexy politicians. This was amply demonstrated by what has been dubbed as the “War on Sex” during the Republican primaries, with candidates vying to outlaw birth control and promote abstinence, ban pornography and act against the “sin” of homosexuality. This has led some bloggers and journalists to compare Republican candidates, such as Rick Santorum, unfavourably to the leaders of Pakistan and Afghanistan.

“If someone wants to ban pornography, make life as hard as possible for homosexuals, and stigmatize sex before marriage… exactly what is it about Sharia law they don’t like?” asks Front Toward Enemy in the Daily Kos.

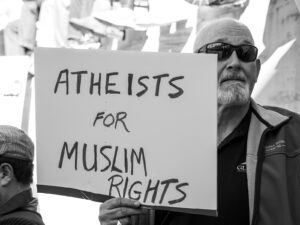

And for all their mutual loathing and belief in a clash of civilisations, in the form of a global “jihad” against Christianity or an international “crusade” against Islam, the Christian and Muslim religious right are fighting on the same side, albeit in different trenches, in what can be called their War against Modernity, especially when it comes to sexuality and gender equality.

Half a world away, Egypt’s first post-revolution parliamentary election was, thanks to the Islamists, dominated by similar issues. Egypt is facing a spate of urgent political, social and economic issues, such as mass youth unemployment, a tanking economy and a cabal of diehard generals who just refuse to call it quits.

But you wouldn’t know it from listening to the discourse of Islamists, particularly that of the hardline Salafist Nour party, who have focused excessive attention on issues of “morality”, including talk of banning booze (as if prohibition has ever worked or Islam ever actually stopped Muslims from drinking), prohibiting or restricting bikinis and censoring “sex scenes” in Egypt’s vibrant film industry, known as the Hollywood of the Middle East.

Although brave women from all walks of life have been at the forefront of the popular uprising and are treated as relative equals by the revolutionary youth movement which has orchestrated the revolution, the burden of this moralising, as is often the case, has fallen on the shoulders of women. This has led Egypt’s secular, liberal women and feminists to look to the immediate future with a mixture of apprehension and worry.

“When Egyptian media spends hours and hours discussing bikinis and alcohol with presidential candidates, it tells you where women are going,” says Marwa Rakha, an Egyptian writer, broadcaster and blogger. “After the revolution, we saw women exposed to humiliating virginity tests, fired at, beaten up, arrested, molested, and stripped naked by army officers. Why would I be optimistic?”

But why is Egypt’s Islamic right so obsessed with sex and women, and seems to view both as the root of all evil?

One reason could be that with all the apparently insurmountable problems facing Egypt, it is a cynical populist ploy. “They want attention, lights, and media presence. How else will they get there unless they talk about women and their evil bodies?” opines Rakha.

“These are issues that people can relate to on a personal level,” explains Karima Abedeen, a secular British-Egyptian living in Cairo. “They are also vague and not quantifiable and most of the people who use these issues as their platform haven’t a clue about how to solve any of the other, more urgent social and political issues.”

On a more ideological plain, Muslim conservatives have quite successfully painted sexual liberty and gender equality as a Western import designed to weaken Egypt’s Islamic identity and corrupt Egyptians, and it is only by embracing Islamic traditions and morals wholeheartedly that Egyptians can resist Western hegemony and recreate their past glory.

“Focusing on issues of morality sends a message to the community that parties like the Muslim Brotherhood and the Salafis will protect our Islamic identity against the Western identity which liberals try to promote,” observes Gihan Abou Zeid, an Egyptian activist and feminist who is working on a book about the women who took part in the revolution. “Many Egyptians believe that following Islamic orders would fix many of the current challenges that Egypt is facing.”

In this, Islamists and their supporters are confusing the symptoms with the disease. In addition to complex international geopolitics, the reason Egypt has not made sufficient headway is not because it has veered too far from tradition, but because it has not embraced secular modernity enough and is suffering from the relative marginalisation not only of women but of young people too.

Moreover, similarly to Christian fundamentalists, Islamists and other social conservatives are alarmed by the corrosion of the traditional patriarchal order caused by the increasing emancipation of women. The loss of centuries of male privilege, especially in the public sphere, that this entails fuels the panicky public fixation on and obsession with what should be private issues, such as virginity and promiscuity. In this world view, strong, independent women are regarded with suspicion, as if they are carrying a volatile sex bomb that will explode upon contact with freedom and mushroom out to shred the fabric of society in its wake.

That said, despite the clear similarities between Egyptian Muslim and American Christian conservatives, the social context in which they operate is quite different. Egyptians on the whole may not necessarily be more religious than Americans, who seem far less inclined to abandon their faith than Europeans, but Egyptians interpret their faith far more traditionally.

Additionally, secularisation has progressed far more in America than in Egypt, where it has been partially discredited through its association both with Western neo-imperialism and the corruption and failure of Egypt’s secular dictatorships. In addition, American Christian fundamentalism is a strong movement founded on freedom and imperial swagger, whereas Egyptian Islamism is a reaction to weakness and decline, where people who have, for decades, been stripped of power in society focus on those few areas on which they can exercise control, i.e. “morality”.

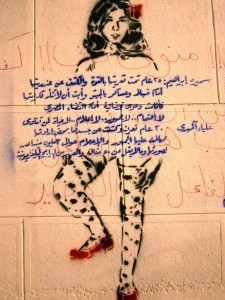

This means that, whereas religion is a fairly flexible and personal affair in America, in Egypt, by contrast, religion, or tradition, is more often than not about conformity and rigidity. And those who challenge this hegemonic view often suffer greatly for their “indiscretion”, as witnessed by the massive overreaction by Egyptian society pretty much in its entirety to the decision by a bold art student, Aliaa Elmahdy, to post naked images of herself on her blog to protest the growing Islamisation of society and demand her freedom of expression.

This traditionalist mindset could also partly explain the paradox that, although millions of Egyptian women have entered academia and the workforce, often outdoing and outperforming men, they have not become sexually freer but have had to compromise by stressing their “virtue” through such coping mechanisms as the hijab. As men lose control of women in the public sphere, they try harder to control them in the family, suggests Abou Zeid.

In fact, it would seem that, in Egypt, secularists, although they view women more as their equals, share the Islamists fear of female sexuality and their objectification of the female form. “The secularists and the conservatives are two faces of the same coin when it comes to women,” concludes Rakha. “Most of the politicians in both currents objectify women – one side wants to cover us and lock us up, while the other wants to strip us naked and show us off.”

Be that as it may, it would be a mistake to view the attitudes and agendas of secularists, many of whom believe in relative gender equality, and Islamists towards women as being identical. Moreover, even the Islamist camp is split between the right-of-centre and heterogenous Muslim Brotherhood’s Freedom and Justice Party (FJP) and the “Tea Party” Salafis. For example, Abou Zeid points to the fact that the Brotherhood is not against women working, albeit within limits, but the Salafis want them to “return” to the home.

The Salafis, she also adds, want to force women to cover their faces, as demonstrated by their vigilante “morality police” which has been roaming rural areas of Egypt, though, fortunately, Egyptian women have been fighting back.

Some are even more equivocal. “The Salafis are mad. They represent the very, very dark ages. The Muslim Brotherhood are not all bad,” says Abedeen. “I think the fact that the Salafis exist should push the Muslim Brotherhood towards a less conservative approach.”

In addition to the likelihood that the FJP will align itself to liberal, albeit economically conservative, parties, the wind is not yet out of the sails of the secular revolutionaries who have so far spearheaded change in Egypt, as illustrated by the defiant “Revolution Continues” movement.

One consequence of the revolution is that it has empowered the previously marginalised, namely the young and women, and made them believe that they can be agents of their own destiny. “Attitudes towards women are better among the young generation, particularly the middle class, to which most of the politically active women belong,” notes Abou Zeid.

This is bound to widen the gap between the young generation and secularists, on the one hand, and older generations and traditionalists, on the other, leading to a more polarised social landscape. “I think that women’s attitudes towards themselves have changed,” observes Abedeen. “The new generation of women is much stronger than older generations and is much less willing to compromise.”

Abedeen also believes that, once Egyptians see what the Islamists are like in power, they will soon fall out of love with them. “I am trying to stay positive and tell myself that it is natural that people should gravitate towards a more conservative option, hoping that these people will not be corrupt,” she says. “I am hoping, down the road, that people will realise that is not the way forward for Egypt, but we will have to see.”

But when all is said and done, it will be largely up to Egyptian women to carve out their rightful place in society. “Looking at Egypt now, I see a lot of courageous defiant women, but I also see millions who realise how oppressed they are yet do nothing about it,” surveys Rakha. “It is up to each woman on her own, in her house, at her desk, in her car, on her way to and from places. This is an individual fight whose collective gains and losses will reflect on the status of Egyptian women.”

A version of this article was published by Salon on 23 January 2012. This article is part of a special Chronikler series to mark the first anniversary of the Egyptian revolution.

Thought the cycle of blokes being the boss and women second-class citizens was kinda..over

“I won’t tell you that the world matters nothing, or the world’s voice, or the voice of society. They matter a good deal. They matter far too much. But there are moments when one has to choose between living one’s own life, fully, entirely, completely—or dragging out some false, shallow, degrading existence that the world in its hypocrisy demands. You have that moment now. Choose!” ― Oscar Wilde

…individualism is vilified in the whole moslem world!

In the whole arab world, it’s all about conformity…individualism is shunned and demonized everywhere on all sides…a pre-modern culture!