Confessions of a would-be Egyptian revolutionary

By Khaled Diab

Returning to Egypt for the first time since the revolution, an expat desktop rebel discovers the inspirational, the troubling and the simply bizarre.

Thursday 26 April 2012

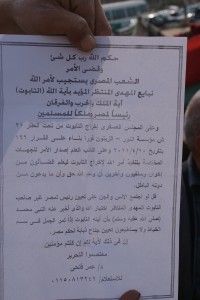

“The next president of Egypt will be the Mahdi,” Dr Omar, who claimed to be a paediatrician who had treated injured protesters on Tahrir Square, told me. In his hand, he held up a petition calling on the government to dig up, at a precise location in a poor Cairo suburb, the Ark of the Covenant because, he claimed, it contained the Mahdi’s identity.

At first, I simply assumed that the good doctor and his not-so-merry crew, who stood on the tented central island of Tahrir Square, were using the sharp wit and humour that have been part and parcel of the revolution to mock the anti-democratic tendencies of the military junta still running the show. But after a little extra probing, it dawned on me that they were deadly serious and they expected the messianic Mahdi to return and reclaim his earthly throne by becoming president of medium-sized Egypt, rather than, say, the United States or China.

This was not quite what I had been expecting to hear on my first visit to Tahrir Square since the Egyptian revolution began in January 2011. Although when I last departed Egypt, a few short weeks before the now-legendary uprising, I was feeling pretty sick of home, and all its corruption and cronyism, with my wife and I speculating about what kind of a second homeland awaited our son. Less than a month later, I began to feel homesick. Even though I’m not into patriotism and I regard nationalism to be safe only in small doses, nonetheless, in addition to the humanist admiration for the underdog, the revolution awoke in my a certain amount of national pride and I longed to be with the protesters rewriting their history.

But I was in the wrong place at the right time, and the best I could manage was the whole-hearted support of the sympathetic spectator. Of course, I could have followed the example of some expatriated friends who, in their haste to return, almost parachuted into Tahrir. But at the time, I was temporarily on my own holding the baby, and then came our move to Jerusalem and… and… and… perhaps I simply wasn’t really a hands-on revolutionary.

May be I also felt a certain unworthiness. Sure, in my journalism I had for years harshly criticised all that I saw wrong with the Egyptian regime and society and dreamed – or wishfully fantasised, as some alleged – of a free and democratic Egypt of social and economic justice for all.

But these newspaper columns, though they could have come crashing down around my ears during one of my regular visits, also supported the ivory tower which afforded me, the expat Egyptian with a foreign passport who was working mostly for foreign outlets, relative protection. So, while I had spilt rivers of ink pontificating, intellectualising and agonising, millions of Egyptians were actually demanding their freedom, dignity and hope, and paying for it with their blood, sweat, tears and fears.

This emotional baggage could perhaps explain why I entered a futile debate with these Mahdist maniacs on the messianic margin, and even got threatened with violence by a couple of them in the process, rather than just walking away scratching my head. Then again, sometimes my mouth is just bigger and my tongue sharper than the weights and pullies that are meant to keep them under control.

Moreover, Tahrir had finally, thanks to the combined will, determination and courage of millions of protesters, lived up to the promise of its name, liberty, freedom. And so if Tahrirites were to endorse the presidential aspirations of anyone, it should be a candidate with some democratic credentials, not an unelected spiritual leader whose rule, benign or not, would be tantamount to a divine dictatorship.

Of course, the unprecedented display of people power deposing the country’s anointed pharaoh-in-chief and the unpresidented prospect of Egyptians actually choosing their own leader may have been too much for some to absorb, and a “miracle” like this is bound to awaken millennialist ideas in the quackier reaches of society.

Even in more “sensible” and “rational” quarters, some worrying signs of antidemocratic tendencies could be seen, such as the pro-stability Egyptians I came across who express support for the Vladimir Putin of Egyptian politics, the mysterious and shady Omar Suleiman, Mubarak’s right-hand man and Egypt’s chief of military intelligence, as the country’s next president because they think he’s a “real man” who can restore order to the country and, with his vast insider knowledge, manage its transition.

Even a top newspaper editor who had spent his entire career opposing Mubarak surprised me by expressing his view that it was time to curb the revolution and work towards stability, otherwise the country would go to the dogs. He said former Arab League chief and one-time foreign minister Amr Moussa was his choice for president. And Moussa’s age and ties with the former regime did not seem to bother him. “If Moussa proves incompetent or unworthy, we can always change him at the next elections. The days of lifetime tenure are over,” the editor argued. When I quizzed him about what he thought of the revolutionary youth making all these sacrifices and so far getting nothing in return, his response was pretty cold and unsympathetic. He blamed the revolutionaries’ refusal to end the revolution and “play politics” for their own demise.

Though I was aware that the elation of the early days of the revolution had been replaced by caution and concern, it was disappointing to arrive in what had once been dubbed the Republic of Tahrir by elated protesters to find time had transformed the beautiful utopian state in the centre of the city back into an ugly, traffic-choked and crowded plaza. Perhaps this dread, as well as the desire to soak in any changes which may have occurred, was part of the reason why I had decided to walk the few miles from my family home to Tahrir, stopping off at some old haunts, including an old cappuccino bar which seemed to be caught in the same time warp I had left it in.

On the way, I encountered some colourful characters, including a man with a toilet brush moustache and sunglasses who claimed to have worked for the former disgraced culture minister Farouq Hosni and believed that, with the right leadership, Egypt could become the richest country in the world, with “85 million billionaires”. So, watch out America, the pharaohs are coming!

On the central island on the Nile known as el-Gezira, as I walked alongside all the plush floating restaurants and past a gathering point for dozens of manual labourers in traditional galabiyas, I caught sight of the first visible topographical change: the burnt-out, grey concrete hulk of the headquarters of the defunct National Democratic Party, one of the symbol’s of the Mubarak regime’s hegemony and the presumed launching pad for his son, Gamal‘s presidential ambitions.

Yes, Tahrir isn’t what it used to be, friends told me. Constant pestering by the authorities and anti-revolutionary forces, friends explained, had driven the vast majority of real revolutionaries away from Tahrir, except when “millioniya” Friday demonstrations were planned.

But signs of the spirit of the revolution and the new, defiant Egypt were all around. In a city whose crumbling walls had once been mostly bare, the colourful explosion of revolutionary street art and graffiti all around were a sight for sore eyes. One wall just off Tahrir Square had a striking image which merged the faces of the deposed president Hosni Mubarak and the country’s current de facto leader Field Marshal Mohamed Hussein el-Tantawi in a single sinister head.

In a bid to control and limit demonstrations, the military junta had constructed makeshift walls all over the town centre. In a show of peaceful disobedience mixed with civic duty, urban artists had transformed these ugly barriers into attractive murals featuring common streets scenes or even the street on the other side of the wall.

A few blocks from Tahrir, young protesters determined to bring down the junta had set up camp and prepared to dig in for the long haul. On the way to their demonstration, I passed the bizarre sight of police officers, hated for being the shield behind which the regime hid and the fist with which it crushed dissent, protesting outside the Ministry of the Interior, calling for the overhaul of the police force and the weeding out of corruption, complaining about their working conditions and telling the interior minister that “The revolution means freedom”. One of the demonstrators insisted that the police was unfairly smeared and that there are officers who are patriotic and support the aspirations of the people.

A block away, the Ultras, football fans turned revolutionaries, would beg to differ, as one banner which read “All cops are bastards”, succinctly put it. Like young activists throughout the revolution, the Ultras not only flouted the easy assumptions about the apathy and selfishness of their generation, but also about the pettiness and fickleness of football fans. In fact, with football being one of the few mass activities people were comfortably allowed to rally around, the Ultras managed to employ the nationwide networks of supporters, the almost tribal loyalty of fans, and years of experience in pitched battles with the police, all of whom were bastards according to one banner I read, to devastating effect during the 18 days it took to topple Mubarak.

Despite the sombre air evoked by the banners and posters commemorating the 78 fans who died in pitched battles during a recent match in a massacre which the Ultras allege was orchestrated by the regime to punish them for their revolutionary activities, the vibe at the protest was upbeat, rebellious and festive.

Isolated circles of singing converged into a coordinated chorus when one of the biggest voices of the revolution, Ramy Essam, arrived, guitar in hand, to sing some of his own cheeky, sarcastic and defiant songs, as well as the Ultras’ own thundering lyrics of rebellion. They sang about the treachery in Port Said, mercilessly mocked a would-be presidential candidate connected to the old regime, sarcastically apologised to the police for the disruption caused by the revolution, and advised fellow citizens “Keep your head down, hang it low, you live in a democracy, you know.”

Given the machismo of football, the Ultras themselves are all men, but there were also plenty of women in the crowd, from the hip and modern to the hip and traditional. Some of the women in hijab figuratively let their hair down, singing enthusiastically and gyrating their hips vigorously. And standing on the sidelines were a few women in the full face veil known as niqab, singing discreetly along.

The revolution has brought women out in force on the streets, including my own courageous sister who lives the struggle with every pore of her being, where they have stood – and fallen – shoulder to shoulder with men. And this despite the traditional protectiveness of the Egyptian family towards its female members and the additional risks being a woman carry, including the notorious “virginity tests” to which some female activists were subjected last year.

Despite proving themselves the match of men in terms of courage and dedication, women have experienced something of a backlash from conservative circles in society, who seem more willing to accept the right of women to fall as comrades than to stand as equals.

Although most women I know did not expect their status to change overnight and realised that their struggle for full equality would take years to reach fruition, the dominance of Islamist parties in Egypt’s first parliament after the revolution, especially the unexpectedly strong showing of the ultra-conservative Salafi parties, has many secular and reformist women spooked.

“Salafists want to reduce the age of marriage and to segregate women and men in the workplace. This gives you some idea of their priorities,” noted Gihan, a feminist who will soon be publishing a book about the women of the revolution. Seated in an outdoor restaurant located on a tranquil island on the Nile which seemed a million miles away from the nearest revolution, Gihan admitted that she was troubled by what kind of future might await her teenage daughter, though she expected and hoped that the revolution would still manage to deliver improvements for women in the longer term.

A promising sign is the extra confidence, even swagger, with which many women now seem to be carrying themselves. Even young women in the hijab, who used to be the coyest group when I was at university in the 1990s, now are out in force late into the night, dance in mixed groups at concerts, as I witnessed at a concert by the satirical fusion folk band Salalem, and some even walk arm-in-arm with their boyfriends.

Hoda, Gihan’s academic friend who was sitting across the table, tried to find a silver lining. She noted that despite all the bad press Salafists received, their women had achieved a partial sexual liberation of sorts. “They are well-read in Islamic jurisprudence and take seriously the rights to sexual gratification and foreplay it guarantees them, and many of them demand divorce if their man doesn’t satisfy them,” she noted.

This led me to reflect on how Egyptian society, in a desperate bid to avoid “decadent” Western ways has revived a number of old-fashioned “decadent” Islamic ways to enable couples to have sex or to live together, such as Zawaj Misyar, which is a no-strings-attached “marriage” entered to allow a couple to engage in sexual relations. But such convoluted attempts to cover sexual freedom up in an Islamic veil, not to mention the traditional approach of turning a blind eye, often lead to dishonesty and hypocrisy in social relations.

But it is not just women that are worried by the Islamists who, like politics itself, have become the talk of the town. Christians and secularists are nervous too. I was sitting with a group of the two in a downtown watering hole appropriately named Houriya (Liberation) which was part traditional teahouse and part boisterous bar fully visible to passersby.

As we choked on the smoke of a hundred fuming political conversations in the tightly packed bar without ventilation, I wondered what the Islamists made of such public displays of boozy merrymaking. As we joked about the ubiquitous campaign of the popular Salafist presidential hopeful Hazem Abu Ismail and speculated about what kind of future the Islamists might have in store for us as they battled with the secularists and military junta to dominate the drafting of Egypt’s new constitution, a solitary drinker at the next table who appeared to be drowning his sorrows, joined our conversation.

Introducing himself as Andrew, he told us how he had been working for a moderately Islamic satellite TV channel aimed at young people which had recently been taken over by Salafists. On the day of the takeover announcement, they promptly gave him his marching orders because, his boss told him in private conversation, Andrew’s religion did not match the channel’s new orientation.

“I don’t understand how my religion affects my role as a director,” he complained, as he fiddled with his purple-rimmed glasses. “Youssef Chahine made some of the best films about Islamic themes, including the victories of Saladin over the Crusaders, and he was Christian.”

While we agreed with this principle and that he should pursue a case of unfair dismissal, one of my friends pointed out that if he had stayed on he may have been forced to make programmes with which he would have been uncomfortable.

“I don’t care about compensation, I just want to make sure that what happened to me does not happen to others,” Andrew said a few nights later, when he turned up at the same bar while an atheist friend and I were talking religion. Informing us that he had spoken to a lawyer, he expressed his determination to stay in Egypt, at a time when thousands of other Christians were fleeing due to all the uncertainty and their vulnerable position.

Talking to Andrew, like other conversations with Christian friends, was making me gloomy. Egypt at its best, and the Egypt I am fond of, is a place of pluralism where one’s religion only matters in one’s place of worship. Naturally, I have long been aware, with the spread of inequality and Wahhabi-inspired conservatism, that Egyptians who think like this have become a rapidly dwindling group, as reflected by a spate of recent attacks on churches, including one just weeks before the revolution, on New Year’s Eve, the day I had last departed the country, feeling down.

But I had hoped that the show of national unity following this horrific bombing, during which Muslims formed human shields around churches, and the spirit of equality and solidarity the revolution awoke would help Egypt turn a new leaf. But we have still not reached this new chapter of full tolerance.

Another minority which prior to the revolution almost dared not speak its name and still has an uncertain and vulnerable future in Egypt are atheists and other non-believers. In fact, so deafening was the silence of most that some readers of my column in The Guardian believed that I was the only one. Some decades ago, atheism was an accepted position, even if ordinary Egyptians frowned upon it, as can be gleaned by the number of writers and intellectuals who openly expressed atheistic and/or anti-religious views, especially between the 1950s and 1970s. However, in recent years, an unholy alliance between intolerant Islamists and a discredited regime desperate to garner some legitimacy as a protector of Islam led to a number of high-profile cases against freethinkers, mostly liberal believers, for allegedly “insulting” or “disparaging” Islam or religion which effectively silenced the vast majority of sceptics and non-believers in the public sphere.

But the trend that started over the past few years of sceptics defying such intimidation to voice their views has accelerated since the revolution, and the number of people who I have come across who openly express their lack of belief has grown significantly – and we even sat in cafes speaking irreverently and in no hushed tones about our views of religion and God. However, their future freedom of expression hangs in the balance.

But this dichotomy between Islamists and secularists is a false one and a convenient sideshow to enable the powers that be to continue to exercise control, insist some activists. Hossam, a prominent human rights activist, told me over his bubbling shisa with its sweet-smelling smoke, that the real division we need to consider is between democratic and anti-democratic forces.

There are Islamists who believe in freedom of belief and expression and gender equality, he pointed out, while there are secularists who are religious bigots and misogynists. I got a taste of this on Tahrir Square when an Islamist stood up for my freedom of belief by telling a youngster who was angry at my criticism of religion that I was free to express what opinions I wanted, even atheistic ones.

For Hossam, the true battle lines for the coming period lay in establishing the rule of law, protecting vulnerable groups and minorities, making the military and intelligence services fully transparent and accountable, and achieving greater social and economic justice. And he is confident that these are battles which can be won, as reflected by the growing political literacy of ordinary people too often dismissed as novices who are taking the fate of their workplaces into their own hands and even campaigning for their local environments, a pursuit once seen as “elitist”.

Others see the Supreme Council of the Armed Forces, the shadowy junta managing Egypt’s revolutionary transition, as the greatest immediate threat facing the country, because though the Mubarak regime may have lost its head, in more ways than one, its body is still largely intact, armed and dangerous.

The road to democracy in Egypt is a long and perilous one, and the road to revolutionising Egypt’s social and economic system to make them fairer and more equitable is yet longer still. The way ahead is filled with uncertainty and pitfalls that can potentially derail the aspirations awoken by Egypt’s young revolutionaries, but the genie of freedom, dignity and equality is out of the bottle and there is no way that any power can banish it. Though they may fight, delay and procrastinate, they cannot avoid the inevitable, that Egypt’s people will one day be free.

You have been busy Khaled! ‘Genie of freedom’ … classic.

Thanks, mate 🙂 Perhaps I should’ve also added the spectre of repression and the demon of despotism for good measure!